Col. Sudhir Farm

Snippets from the Visitors' Book

The Kota tonga trail was a real highlight - a bit like a 19th Century treasure hunt. It’s full of little nuggets of unusual information and fascinating glimpses into the unsolved mysteries of Kota.

Harriet and Will, London. UK

The memorial to Major Burton and his sons was much more moving than the Taj Mahal or the lake at Udaipur, marvellous as they are.

Henry Vane, Cumbria, UK

1857 Kotah Uprising - The Tonga Trail

The year 2007 was the 150th anniversary of the Kotah Uprising of 1857-58. To commemorate this anniversary, we had put together a trail of discovery of the fortifications of Kotah.

The year 2007 was the 150th anniversary of the Kotah Uprising of 1857-58. To commemorate this anniversary, we had put together a trail of discovery of the fortifications of Kotah.

The guided trail we organised was in a horse-drawn carriage called a tonga. Our guided tour started and ended at Sukhdham Kothi, the house which was built for the British Surgeon soon after 1857.

Though this guided trail was specially for the anniversary, it may still be possible to organise it for our visitors, but we cannot guarantee it.

The original fort, or Garh, at Kotah was built on an excellent strategic position on high ground on the right bank of the river Chambal, at the point where the river emerges from a deep gorge. Overtime further walls and fortifications were added right up to the beginning of the twentieth century which came to enclose the walled city of Kotah. These walls and fortificaitons were well maintained until India’s independence in 1947 when Kotah State was absorbed in the Union of India and the justification for their upkeep lost its immediate relevance.

The Garh is situated at the southern tip of the walled city and was protected by a series of three concentric walls. Massive gates in each concentric wall can still be seen today which once guarded the flow in and out of the fortified city and allowed for its division into independently defensible enclaves. This fortified city is the backdrop to our Tonga Treasure Hunt.

Our background to the 1857 Uprising starts with Zalim Singh Jhala. Though he died in 1823, his policies may have had indirect influence on what was to follow. He built the outermost walls of the city between 1745 and 1818 to a standard and thickness not found anywhere else in India. The walls are still virtually complete. The inner walls and fortifications withstood a siege lasting two months in 1745 by a combined force of Jaipur State and the Marathas.

Zalim Singh Jhala, the Diwan (Prime Minister) and Faujdar1 of Kotah State, was an astute administrator and visionary. He had started his career as a general and adopted European weapons and founded a gun foundry.

Zalim Singh was appointed Regent in 1771 until the 10-year old minor Umaid Singh came of age to become the Maharao, but stayed on as the de facto ruler of Kotah State for over 50 years. He was a close personal friend of Colonel James Tod, who represented the East India Company in Rajasthan and wrote The Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan. In 1817 Kotah became one of the first states to sign a treaty with the East India Company under Zalim Singh’s leadership. He worked ceaselessly to further the ends of his own family and persuaded the Company to include an amendment to the treaty the following year that gave his descendants the right to be Diwan and Faujdar of Kotah State in perpetuity. This was in recognition of his loyalty and help in defeating the Pindaris2.

Zalim controlled the forces of Kotah State. He appointed a Muslim, Dalel Khan, as the commander-in-chief, rather than giving the post to a Hindu Rajput3 whose loyalties would have been to the Maharao rather than to him. Dalel Khan was responsible for rebuilding and strengthening all the walls and fortresses in the State.

Disagreement between the Diwan Zalim and Umaid Singh’s son, Maharao Kishor Singh, finally led to a battle in 1821 in which the British found that they had treaties with both sides but decided to support the Diwan, who then won. A reconciliation was effected, but there was a continuing power struggle between the Diwan and the Maharao of the day. This was finally resolved by the British in 1838 when they carved up Kotah State and gave one-third (17 parganas or districts) to Zalim Singh’s grandson to be incorporated into a new state called Jhalawar, of which he became the first ruler4. Independent authority for the Maharao had come at a heavy price, but he was prepared to pay it to see the end to the hereditary post of Diwan that Zalim had created. The British arranged a new treaty with Kotah State. The financial tribute was reduced, instead a force of auxiliary troops had to be maintained by Kotah State. This force came to be called the Kotah Contingent and comprised mainly Biharis who were not local people. In 1855 the force consisted of 3000 men stationed in Deoli, 85 kms. north-west of Kotah under British officers and control.

In his unpublished memoirs “Some Reminiscences of My Life”, General Julius B. Dennys the then commanding officer of the Kotah Contingent wrote “The Kotah Contingent was a force raised by ourselves, consisting of Artillery, two 9-pounder guns and two 24-pound Howitzers - horsed, a Regiment of Irregular Cavalry and a Regiment of Native Infantry. There were only three European officers for the whole, a Commandant, a second in command and the Adjutant. The Rajah of Kotah was under treaty bound to maintain this force out of the revenues of his state, but he resented its maintenance by firstly declining to have it quartered inside its dominions.”

In 1844 Major Charles Burton became the Political Agent for Kotah, and spent 13 happy years there until 1857. Early in 1857, taking heed of the uprising in northern India in which many British women and children had been killed, he sent his wife, Elizabeth, and five children to the military station at Neemuch, 128 kms. to the south-west of Kotah, where they had a house. But on June 3rd the troops in Neemuch too mutinied and the Burtons had to flee for their lives. In the process they lost all their possessions. Major Burton and remnants of the Kotah Contingent5 at Deoli came to their rescue and saved their lives and the lives of other British women and children as they sheltered in a small fort nearby at Jewud, which coincidentally was under the command of Burton’s eldest son, James. Major Burton at this point doubting the loyalty of the Kotah Contingent, decided to replace them with Raj Paltan troops that had been stationed in Kota. Later he replaced the sepoys on duty at his Agency bungalow in Kotah with irregular forces made up of Baba Nagas6, Dadupanthi7 and Sikh horsemen.

In 1844 Major Charles Burton became the Political Agent for Kotah, and spent 13 happy years there until 1857. Early in 1857, taking heed of the uprising in northern India in which many British women and children had been killed, he sent his wife, Elizabeth, and five children to the military station at Neemuch, 128 kms. to the south-west of Kotah, where they had a house. But on June 3rd the troops in Neemuch too mutinied and the Burtons had to flee for their lives. In the process they lost all their possessions. Major Burton and remnants of the Kotah Contingent5 at Deoli came to their rescue and saved their lives and the lives of other British women and children as they sheltered in a small fort nearby at Jewud, which coincidentally was under the command of Burton’s eldest son, James. Major Burton at this point doubting the loyalty of the Kotah Contingent, decided to replace them with Raj Paltan troops that had been stationed in Kota. Later he replaced the sepoys on duty at his Agency bungalow in Kotah with irregular forces made up of Baba Nagas6, Dadupanthi7 and Sikh horsemen.

In October 1857 the Maharao of Kota requested the return of Major Burton. The Maharao had ordered Jai Dayal8 and Mehrab Khan9 out of Kotah with rebellious elements of his forces and thought he could guarantee the safety of the Political Agent. The British had recaptured Delhi and the Maharao was probably keen to show that he was a supporter of the British. But to the Maharao’s embarrassment Dayal and Khan refused to go. The Maharao sent his lawyer to advise Burton not to continue to Kotah, but he refused and arrived on October 12th with his two youngest sons, Arthur Robert (a twin) aged 20, and Francis Clerke aged 19.

October 13, 1857

Major Burton had an audience with Maharao Ram Singh on his return from Neemuch to discuss the situation

October 15, 1857

About 2000 of the Kotah troops with most of the artillery went over to the rebel command led by Pathan Mehrab Khan and Jai Dayal. They collected a mob and marched on the Agency Bungalow and beseiged it for 4 hours. The newly engaged irregular forces all ran away. The Sikh horsemen did nothing as they were under the impression that since the forces had come from the Garh palace, the Maharao had sent them and it would be prudent to remain neutral. Major Burton and his two sons, Francis (“Frank”) and Arthur were killed as were Doctor Sadler and one or two others, including an Indian Christian, Mr. Saviell, who worked at the dispensary in the city.

The Maharao left the Garh to assist Burton but was persuaded to turn back as he had no control over his troops.

Koela House, home to one of the leading Rajput families, was also besieged, presumably on this date for 2 days. The rebels blew open the wooden gates. The young heir survived somehow, but the other male family members died heroically.

October 16, 1857 Onwards

The Maharao shut himself in the Garh with a handful of loyalists and Garh Zapta troops. He had 9 cannons inside as against 250 outside. The rebels tried to storm the Garh several times but were repulsed. They captured the ferry and boats and took control of the river.

Seth Dan Mal’s haveli (now known as Bapna Haveli) came under attack. He was rescued by Raj Arjun Singh of Kunadi and managed to flee to the safety of the Garh on the back of an elephant, scattering asharifis (gold coins) to distract the rebels.

Over the next weeks loyalists managed to slip into the Garh from the riverside through the Water Gate and swell the numbers.

The people of Kotah, who numbered 35000, lived in constant fear of the rabble which was solely under the command of Jai Dayal and Mehrab Khan.

November, 1857

After the rebels were defeated at Mandsor (near Ratlam in Madhya Pradesh, and the centre of opium cultivation), a sizable rebel force sought food and loot in Kotah, swelling the ranks to 30000. The Nawab of Jhajjar and Naseer Mohammed Khan of Tonk were two of the notable rebels. (On the whole, the Hindu Rulers in Rajputana stayed loyal to the British and did not offer their support to the Mughal Emperor in Delhi. They were rewarded for this after the Uprising.)

January 1, 1858

The rebels held the whole city until the First Offensive launched by the Maharao’s supporters to try and regain Kotah on January 1, 1858. 500 men attacked Patan Pol, a gate in the inner walls, and managed to capture it. Another 500 attacked Kaithooni Pol, a gate further to the south in the inner walls, and although they suffered heavy casualties the loyalists managed to drag 20 captured cannons back to the Garh.

January 18, 1858

1500 infantry arrived at Keshorai Patan from Karauli. The heir apparent of Kotah was married into Karauli and they came to the rescue. Karauli is approximately 200 kms. to the north of Kotah. Keshorai Patan is on the river Chambal downstream of Kotah. (In 1853 the Thakur of Karauli had rebelled and the Kotah Contingent had been called upon to put down the rebellion.)

January 19, 1858

A peace was negotiated at Mathureshji’s Temple, just within the walls at Patan Pol, to last until Holi on February 27th.

January 25, 1858

The Karauli troops camped at Nanta across the river to the north.

February 9, 1858

The Karauli troops landed at Nazar Niwas Bagh, just below the present day Kota Barrage.

February 25, 1858

They were invited into the Garh for a feast and managed to get back to camp safely.

February 26, 1858

Holi was celebrated.

February 27, 1858

The loyalist Second Offensive was launched. 3000 loyalists managed to retake the ferry, the boats and the river. They captured more cannons, bringing their total up to 50. For 25 days the fighting continued unabated and the city was covered in a pall of smoke by day and lit up by gunfire at night.

March 20, 1858

Major General Roberts, GOC Rajputana Field Force arrived at Nanta with 5500 men.

March 21, 1858

Maharao Ram Singh with 200 men managed to slip across the river under enemy fire to meet him. Major General Roberts landed by boat entered the Garh through the Water Gate. He surveyed the City from the Jantar Bastion within the Garh for enemy targets.

March 23, 1858

The British set up a gun battery (Unit 1) at Saketpura opposite the Garh on the other side of the river Chambal, ready to provide covering fire for a troop crossing. Unit 4 was also sited there. Units 2, 3 and 5 were sited at Kunadi, a little to the north from where they could fire across the river at Rampura in the NW corner of Kotah.

March 25, 1858

300 men of the the 83rd Regiment reinforced loyalist troops in the Garh.

March 27, 1858

Major General Roberts and 600 men of the 95th Regiment with two 9-pounder guns crossed over at night. There was heavy bombardment by the British on the rebel gun emplacements.

March 30, 1858

From 01:00-07:00 hrs. one thousand British troops and one thousand Indian troops crossed over the river in boats, and on rafts made from arrack barrels lashed together that had been brought from Ajmer. The combined troops stormed the rebel held city. The British troops went around the outer walls on the inside and took the cannons from behind. It was all over within a day.

Fatehgarh, which was a bastion overlooking the river was captured by Brigadier Mackon\92s group. This is the second bastion along the river Chambal when approaching the Kota fortifications on the left bank from downstream, opposite what used to be the village of Kunadi (Kinari). Here, the 21 year old Lt. Charles Hancock, a sapper with the Bombay Engineers, was ordered to dismount the guns with a party of Royal engineers. While doing so, the magazine in the battery blew up. He died of his wounds two weeks later on April 14, and is probably buried in the British Cemetery at Kotah10. Four other engineers also succumbed in this incident. Ten men of the Royal Engineers and three men of 12th Regiment Native Infantry were badly wounded11.

(6000 rebel men and women escaped but some were captured and the rebel officers blown-up by cannons - their bodies placed or attached in front of a cannon which was then fired. Some of the loyalists, including the vakil (lawyer) who had been sent to warn Burton, were also killed in this way.)

April 1, 1858

Two officers, Captain Evelyn Bazalgette and Captain Robert Bainbrigge, were killed on April 1st by an explosion in a rebel ammunition dump that they were guarding. They are also buried in the British Cemetery at Kotah.

April 4, 1858

The Maharao Ram Singh paid another courtesy call on Major General Roberts to thank him. (Later the Maharao’s gun salute would be reduced from 15 to 11 by Governor General Canning for not having done more to save the agent Major Burton, only to be restored a few years later during the reign of Maharao Shatru Sal II who succeeded Ram Singh)

April 20, 1858

Kotah was handed back to Maharao Ram Singh.

September 17, 1860

Jai Dayal was hanged inside the Agency Bungalow. Burton’s eldest son, James, was instrumental in tracking down his father’s killers. Pathan Mehrab Khan was also hanged after a trial. (One version has it that they were both strung from neem trees while seated on elephants; then the elephants were led away. It is not clear whether they swung or their end was even more gruesome.)

Who were Jai Dayal and Mehrab Khan and how did they persuade the troops to mutiny? In 1857 more than half the troops were Muslim (and thus more likely to support the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zaffar), but Dayal was a Hindu as were many of the rebels. They had a history of being controlled by the Diwan, Zalim Singh, and not by the Maharao. The power of the Hada Rajputs, who would traditionally have been in control of the state forces, had been systematically undermined by Zalim Singh. All the artillery, since the earliest days of the Mughals, had been traditionally manned by Muslims. The Kotah Contingent stationed in Deoli had already rebelled in July 1857 in Agra. Dayal had been employed by the Maharao as Burton’s lawyer and had lost his job due to Burton’s report of his intemperance. He thus had a powerful grudge against Burton. In the heady revolutionary atmosphere of 1857 the troops were ready to be roused. Since the Muslim soldiers had sworn on the Koran that they would be loyal to the Maharao, he believed they would not revolt, rather mistakenly as events were to prove.

The British had already taken Delhi in October 1857. Did the rebel leaders really think that they could wrest the state from the Maharao and divide it up between themselves?

There is also a suggestion that the opium trade may have played a part in the Uprising. Opium was the recreational drug of the time and was routinely consumed before a battle. It was grown in pockets of land by the tribal people of the region who were granted licences, a system that continues to this day. Opium taxing and trading were the backbone of the Kotah economy and the East India Company bought it to export it (despite no mention of this in Colonel Tod’s The Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan). The opium growing areas were lost to Jhalawar when the state was created, which must have caused resentment. At least one Kotah trader had his own wholesale office in Peking. Opium was totally banned by the British in 1899, which was a serious blow to the state economy.

When Major Burton was killed on 15 October 1857, his head was taken in triumph by the rebels and paraded around town before being attached to a cannon and blown up. What happened to his headless body and the bodies of his two sons immediately after they were killed is a matter of conjecture, but at the insistence of the Maharao they were buried in the British Cemetery in Kotah. Whether this happened on 16 October or was a reburial sometime later is not precisely verifiable. They were placed next to the grave of Elizabeth Burton, a daughter who had died in 1854.

When Major Burton was killed on 15 October 1857, his head was taken in triumph by the rebels and paraded around town before being attached to a cannon and blown up. What happened to his headless body and the bodies of his two sons immediately after they were killed is a matter of conjecture, but at the insistence of the Maharao they were buried in the British Cemetery in Kotah. Whether this happened on 16 October or was a reburial sometime later is not precisely verifiable. They were placed next to the grave of Elizabeth Burton, a daughter who had died in 1854.

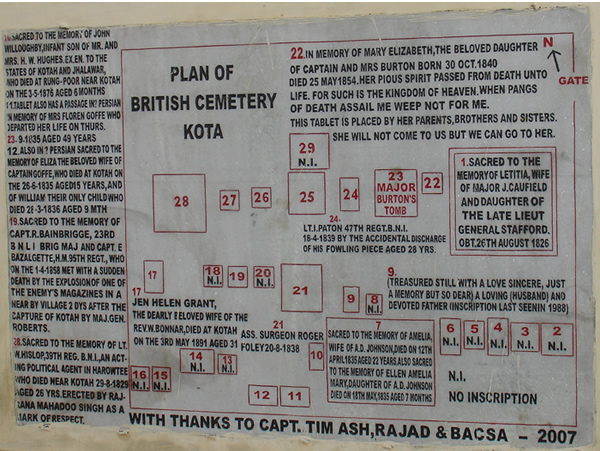

The cemetery is now maintained by the Kota Heritage Society. Here members and guests have been planting shrubs. For details, please contact Victoria via the mailbox.

The cemetery is now maintained by the Kota Heritage Society. Here members and guests have been planting shrubs. For details, please contact Victoria via the mailbox.

Cemetery Brochure:

You can download a copy of the brochure by clicking here. For best results, please download, print on both sides of an A4 sheet, fold and read. We welcome your comments.

Members of the British Embroiders Guild visiting in 2009.

Members of the British Embroiders Guild visiting in 2009.

Plan of the British Cemetery at Kotah drawn up by the Late Capt. Tim Ash in 2007.

Plan of the British Cemetery at Kotah drawn up by the Late Capt. Tim Ash in 2007.

Contemporary Notes on the Kotah Contingent

The following notes are based on “Some Reminiscences of My Life” by General Julius B. Dennys the then commanding officer of the Kotah Contingent.

On December 31st 1856 Captain Dennys was appointed to the command of the Kotah Contingent with a salary of 1,500 rupees a month. He was very much in debt and imagined that in a few years he could get his head above water.

“The contingent was ordered to a place called Deoli, and again we set to work to build lines for the men and houses for ourselves. Mine cost 11,000 rupees. And in 1853 I had sent home our three eldest children. But I had the house and everything in it all of a first-class description, which I imagined to be about 20,000 rupees in value.”

If the British officers found themselves in financial difficulties, the conditon of the sepoys was desparate.

“The contingent under my command were, in the matter of pay and pensions, in a much inferior position to their brethren of the regular army, though performing exactly the same duties.”

“...our men had good reason to believe that if ever an opportunity came of their being employed on active service their grievances in the matter of pay and pensions would be rectified but the cavalry were chiefly composed of Mohamodans. They were almost without exception deeply in debt. The pay of the Sowars (privates) 20 rupees a month, was insufficient for their wants. As a body I always felt that our cavalry could not be relied upon; they were well dressed and very fairly mounted but their general state of indebtedness was sufficient to prevent their remaining loyal.”

“...our men had good reason to believe that if ever an opportunity came of their being employed on active service their grievances in the matter of pay and pensions would be rectified but the cavalry were chiefly composed of Mohamodans. They were almost without exception deeply in debt. The pay of the Sowars (privates) 20 rupees a month, was insufficient for their wants. As a body I always felt that our cavalry could not be relied upon; they were well dressed and very fairly mounted but their general state of indebtedness was sufficient to prevent their remaining loyal.”

The uprising at Meerut started on May 10th 1857. The Kotah Contingent was ordered to march for Delhi and they set off on May 19th leaving 100 sepoys to guard all the women and children. Dennys then received orders to march for Agra. “At Agra itself the Native Troops had been disbanded and allowed to proceed to their homes, which, in nine cases out of ten, probably meant that they joined the rebels.” The Contingent restored order at Mathura on the way to Agra.

The news arrived that the troops at Neemuch had mutinied and en route for Delhi had sacked Deoli, burnt the cantonment and captured all the wives and children. (In fact the European families had been rescued before the attack and were being looked after in Jodhpur and Udaipur) The Neemuch rebels changed course and headed for Agra with their hostages. This put a great strain on the loyalty of the troops.

Captain Dennys begged for his men to be disarmed but was ignored. On July 4th the Contingent was ordered to march against the Neemuch mutineers. The officers felt that the Agra authorities were as much as forcing the men to mutiny. Once in position, a violent dust storm arose. In the chaos a cavalry Sowar tried to shoot Dennys but missed. A Havildar of the artillery deliberately shot a British Sergeant and fired at Dennys. Some of the Infantry wept and begged their officers to leave them. The main body of the Cavalry galloped off to join the Neemuch mutineers. In despair, the remaining officers fled to Agra and joined the 2000 women and children sheltering in the fort.

“By July my own men had mutinied and I was without employment on a bare Captain’s pay. My house and every single thing in it had been burned to the ground. I was a beggar and some 40,000 rupees in debt, and could not see a ray of light which might help me through.”

In this picture, the young woman on the right, is the Gt Gt Gt Gt Granddaughter of Capt. Julius Dennys, the Commanding Officer of the Kotah Contingent in 1857 and is named after his wife. She is my niece, and is seen here with my sister Frances besides Major Burton’s tomb.

Footnotes

1The post involved raising troops and collecting revenue.

2The Pindaris originated as Muslim irregular cavalry who operated as mercenaries and extracted tribute. The East India Company finally gained the upper hand and forced them to disband in 1818. One of their ablest leaders Amir Khan was settled at Tonk as a Nawab.

3Rajputs were the Warrior caste and were Hindu. They could be expected to be loyal to the Maharao.

4In 1899, 15 parganas would be returned to Kotah State by order of the Privy Council in London.

5In June 1857, most of the Kotah Contingent was sent to Agra to suppress the troubles, but mutinied when ordered to meet the mutineers from Neemuch who had reached Agra on July 4th of the same year and who held the Kotah Contingent men’s families as prisoners. Burton marched with the remnants whose continuing loyalty would have been suspect.

6Monks, trained in martial arts, who were followers of Shiva.

7Followers of the 16th century mystic Rajasthani saint Dadu and thus also Hindu.

8Jai Dayal bore a grudge against Burton who had caused him to lose his job as a lawyer.

9Mehrab Khan had fought for the British in the past as an infantry commander and had been one of Zalim Singh’s most loyal supporters. He wanted to take over Kotah State and divide it with Jai Dayal.

10Olive Crofton in her book published 1934 lists Lt. Hancock’s grave as being in the Kotah British Cemetery.

11This account of events at Fatehgarh is taken from a report of Maj. Gen. H.G. Roberts GOC, Field Force in Rajputana (National Archives, New Delhi: 28 May 1858, No. 67 of 1858 Ref. 711-14)